Annie Kenney

Early Life

Ann Kenney ‘Annie’ was born in Springhead, Oldham on 13 September 1879, the fifth child of Horatio Kenney and Ann Wood. Both parents worked in the nearby cotton mills.

Annie described how her mother’s philosophy was to 'see the best in anyone and the worse will gradually fall away. Be kind to others, tolerant and sympathetic. We were never allowed in her hearing to say either unkind things about others or to abuse others in any way.' Ann’s death in January 1905 clearly devastated the family, and Jessie Kenney, Annie’s younger sister signals it as the point at which the family broke up.

Horatio appears to have been something of an introvert, preferring the company of his livestock or a walk on the moors to the animated discussions that followed high tea on Sundays. He was recognised locally as an expert in folk medicine and the care of animals. For most of his life he worked in the cotton mills, save for an ultimately unsuccessful venture into business as a stationer.

Annie went to the village school from the age of five, leaving at age ten to work in the local mill. She 'received the news with mixed feelings…glad to escape the hated school lessons…but [with a] fear of the new life.'

She wore clogs and a pinafore to work and lost a finger in an accident. She initially worked half time, returning to school in the afternoons but by age 13 she worked full time. Despite working almost 12 hours a day at the mill, Annie, encouraged by her mother, developed a love of literature, including Walt Whitman, and a notebook in the archive records youthful efforts at story writing. She recalled that the only thing she liked at school was poetry.

Annie described how her 'home-life was happy. Our one trouble was that we had to retire much earlier than the other children of the village… I can still see our home with its bright, roaring rosy fire, and all the children, including myself, sitting on the window-sill watching the lights of the cotton factory, a few miles away, gradually going out. Those lights were our signal to retire… On Sunday evenings mother read us stories. They all seemed to be about London life among the poor...'

Activism

Annie was influenced and inspired by the writings of Robert Blanchford in The Clarion, a weekly socialist newspaper. In 1905, not long after her mother’s death she heard Christabel Pankhurst and Theresa Billington speak. It was the first time she had heard about ‘Votes for Women.’ She agreed to hold a meeting for women factory workers and was invited to tea at the Pankhursts. Annie spent the summer of 1905 travelling around Lancashire speaking for women’s suffrage.

On Friday 13 October, Liberal grandees, including Sir Edward Grey and Winston Churchill, were campaigning in Manchester, holding a meeting at the Free Trade Hall. Annie and Christabel decided to ask ‘if you are elected, will you do your best to make Woman Suffrage a government measure?’ Annie arrived at the meeting with a home made banner, declaring ‘Votes for Women’, hidden in her clothes. Annie asked the question and was ignored. She asked it again and was pulled back into her seat. She then unfurled the ‘Votes for Women’ banner, for the first time and the two women were dragged from the meeting. Christabel, knowing that they had not done enough to secure imprisonment, spat at a policeman and the two were imprisoned at Strangeways prison for seven days, after refusing to pay a fine. They also secured a piece in The Times.

Annie never returned to the mill. In 1906, she left Manchester ‘to rouse London’ and lived and worked with Minnie Baldock, an East End social activist. Together, they created the Canning Town branch of the WSPU, the first in London. Annie was paid £2 a week by the WSPU. In these early days of the militant campaign, Annie demonstrated an ability to carry our daring and high profile stunts, unfurling banners at the Albert Hall, ringing incessantly the bell of the Chancellor of the Exchequer. She was also an effective organiser and a charismatic speaker, drawing both recruits and donors to the cause.

In 1907, she moved to Bristol to set up the WSPU’s West of England branch. She stayed there until 1911 and organised a number of highly effective protests. Many of the women who had trees in the Blathwayt plantation were her colleagues in the West of England. Elsie Howie and Vera Holme hid in the pipe organ at Coulston Hall to disrupt a political meeting. Mary Phillips attacked Winston Churchill at Bristol train station and Annie organised a group pf women to travel around on a caravan to avoid the 1911 census. She recruited Mary Blathwayt to the WSPU and spent many of her weekends at Eagle House, resting from her busy schedule.

In the spring of 1912, the WSPU leadership was arrested. Christabel fled to Paris and Annie ran the organisation in London, travelling each week to Paris to receive instructions. Rachel Barrett became her Deputy. By this stage, the militant movement had begun increasingly violent tactics, such as window smashing. When the WSPU split, Annie had an agonising choice between Christabel and the more moderate Pethick-Lawrences, with whom she had a close relationship. She chose Christabel and militancy.

When Annie was arrested in 1913 for incitement, she received a sentence of 18 months and was imprisoned in Maidstone jail. Her health soon suffered from hunger strike and she was the first woman to be release under the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’ where a hunger striking woman was released to prevent a death in a jail and then, once she was recovered, re-arrested. In all, Annie was arrested 13 times.

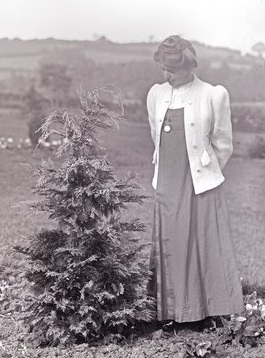

Annie was the first woman to plant a tree, a conifer, in the Eagle House plantation, on 22 April 1909. On the same day, Constance Lytton planted her tree. The plantation was named 'Annie's Arboretum' by the Blathwayt family who wrote her with updates of its progress.

Later Life

In 1914, the WSPU suspended all militant activities on the outbreak of World War I. Annie went to the United States on a lecture tour, returning to encourage women to become munitions workers. During the war years, she became an insider, close to David Lloyd George and, after 1917, spoke on anti-communist platforms. She worked hard for Christabel’s unsuccessful parliamentary campaign 1918. After the war, she lived for a while with fellow suffragette Grace Roe at St Leonards on Sea, where she wrote an unpublished pamphlet on famous British women. This is in the archive.

In 1920, she married James Kenney and they settled in Letchworth with their son Warwick Kenney-Taylor. Annie wrote her autobiography Memories of a Militant which was published in 1924. She effectively retired from politics at this stage, although she would occasionally write to the press or engage on issues such as the erection of a statue of Christabel Pankhurst.

She maintained a correspondence with former WSPU colleagues such as Christabel Pankhurst, Flora Drummond, the Lyttons and Pethick-Lawrences. Unlike other former suffragettes, she largely avoided talking to historians and chroniclers but was hurt when her legacy was downplayed. In particular, she was horrified at her depiction in a 1951 radio play, hating being sidelined as the working class mill girl.

Her energy at this time was spent studying the Rosicrutian faith. She wrote an account of her spiritual journey before her death, but which failed to secure publication.

Annie died in 1953 and her ashes were scattered on Saddleworth Moor.

Quote

“Though I had no money I had reaped a rich harvest of joy, laughter, romance, companionship, and experience that no money can buy.” Annie Kenney, recalling the day women won the vote in 1918.

Read Sara Taylor's short story, dedicated to Annie and Jessie Kenney.